By Paul S. George, Ph.D.

The early months and years following the city of Miami’s incorporation in 1896 were filled with promise and growth. By summer’s end, 1896, the new city already had a moniker: the “Magic City,” a name given it by Ethan V. Blackman, a publicist, ordained minister and writer who had never visited Miami, but who was swayed by the enthusiasm of Henry M. Flagler, who extolled the nascent community’s virtues and promise to him in a highly descriptive letter.

The ”magic” continued into the Christmas holidays of 1896, when the recently opened Hotel Miami hosted a large number of guests who enjoyed the sounds of music from a small musical combo while the nascent city basked in the satisfaction of its quick start. A few blocks east of the Hotel Miami was the rising Royal Palm Hotel, whose opening was set for January 1897.

To bring the Royal Palm Hotel to fruition several developments had to first take place, beginning with clearing the land at the construction site. The most notable feature of the site was a tall Indian burial mound, said to stand about twenty feet in height, with the remains of scores of persons buried there over an undetermined period of time. John Sewell, who headed the Flagler organization’ s work in creating West Palm Beach, was assigned the task of clearing the land for the hotel and overseeing its construction after his arrival in March 1896. Sewell maintained in his autobiography that the mound ”stood up like a small mountain from the bay.” He employed initially a twelve man work force comprised of African Americans. After clearing the remainder of the site, construction was ready to begin.

On Christmas Eve, 1896, a few weeks before its opening, John Jacob Astor IV and his son, five-year old William Vincent Astor, visited the unfinished Royal Palm Hotel. The scion of the uber-wealthy Astor family whose fortune was traced to a flourishing fur trading business reaching back to America’s colonial era, John Jacob Astor was one of the wealthiest persons in the world.

John and William Astor arrived at the unfinished hostelry on Christmas Eve. Workers and hotel staff were attentive to their needs, providing them with a room, as well as a makeshift Christmas tree, after felling a Dade County pine and decorating it in an effort to impart a sense of yuletide spirit for young William Vincent. The next morning, the youngster, adorned in a sailor suit, ran into the lobby and found, magically, under the “Christmas tree” presents from Santa Claus. Sadly, the life of his father, John Jacob Astor, was cut short when he perished on the ill-fated RMS Titanic in April 1912.

The Magic of Miami suffered a major blow the morning after Christmas 1896, when a ruinous fire, apparently triggered by the pyrotechnics celebration of the night before, damaged or destroyed many of the wood frame buildings bracketing the new city’s most important street, Avenue D, today’s S. Miami Avenue. The city rebuilt quickly in its aftermath with its center now moving to Twelfth Street, today’s Flagler Street, which intersects with S. Miami Avenue.

In the meantime, Flagler’s magnificent hostelry, which stood five stories in height, with a central rotunda reaching six stories, towered over a city of one story, wood frame buildings, opened on January 17, 1897, an event that buoyed the feelings of its citizenry in the aftermath of the ruinous fire. Its exterior bathed in “Flagler Yellow”, which was said to be the railroad titan’s favorite color, the Royal Palm Hotel was a massive concoction of color and design elements. It offered 450 rooms, a mansard roof and a 578-foot veranda that wrapped around the eastern portion of a building stretching for nearly 700 feet. Hundreds of mature coconut palms dotted the grounds, while a separate bathing casino featuring a large swimming pool representing just one of the striking amenities offered by the hotel.

Opening night featured a dinner amid an elegant setting of fresh flowers and gleaming crystal. The menu offered green turtle soup, baked pompano and dessert from a French pastry chef. Soon the roster of visitors to the posh hostelry would include the Rockefellers, Carnegies and Vanderbilts.

Photo of the Royal Palm Hotel taken in 1917. South Florida Photograph Collection, HistoryMiami Museum archives.

While other new residents did not carry the cache of the above titans of industry, they did impress by their sizable numbers and passion for their new home. Their arrivals pushed the neophyte city’s population to 1,681 by 1900.

Included in the ranks of “newcomers” was the Burdine family, headed by William Burdine, a merchant who would build his Burdine department store into one of the city’s most important businesses. Burdine was drawn to the Magic City after experiencing success selling clothing and other goods to military trainees who came here during the brief Spanish-American War, a conflict fought in 1898 over the issue of Cuban independence from Spain.

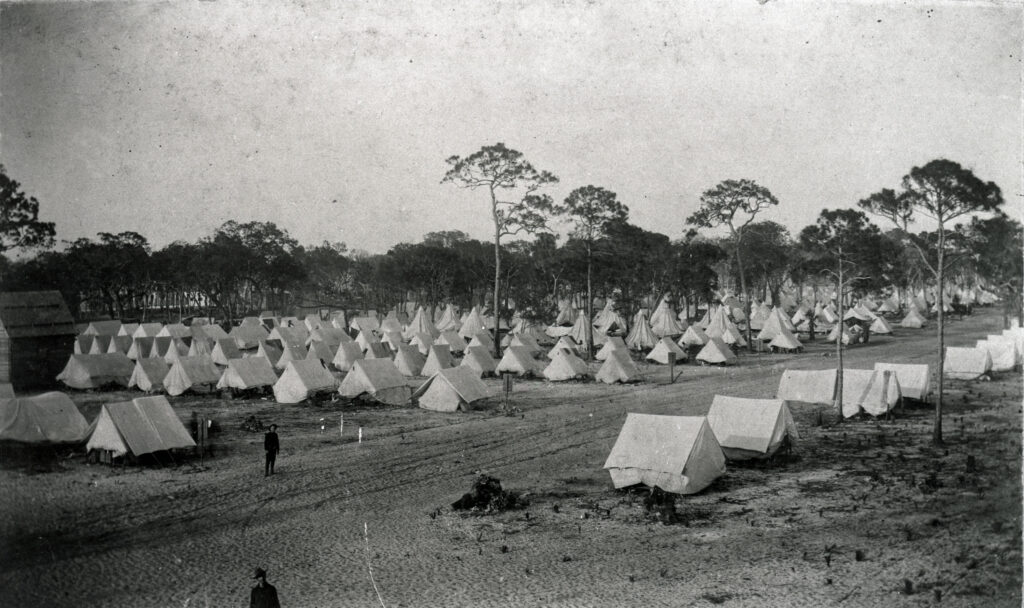

Camp Miami, which stood on the northeastern edges of downtown, was a woefully inadequate training ground for 7,500 volunteer warriors in that summer of 1898 as fighting in Cuba raged. The presence of thousands of troops from Alabama, Louisiana and Texas was a mixed blessing. Their presence was great for business, but disastrous for law and order, as fights led to homicides among troops and the general population. Illnesses from dysentery and other causes led to the death of hundreds of trainees.

With the war over by summer’s end 1898, soldiers broke camp and returned to their home states without ever reaching Cuba and the theater of war. Shortly after the end of Camp Miami, Julia Tuttle, Miami’s “Mother,” died after suffering intense headaches over a lengthy period. A shocked city, led by its business class, suspended activities during the period of Julia’s funeral and burial in the Miami City Cemetery north of the city limits.

Photo of Camp Miami taken in 1898. South Florida Photograph Collection, HistoryMiami Museum archives.

As of if these dislocations and loses were not enough, the city experienced a yellow fever epidemic in the Fall of 1899, which led to its quarantine for three months. Nearly 200 persons contracted the scourge, with fourteen perishing from it. Yellow flags waved from the rooflines of residents stricken with “yellow jack,” warning that a sick person was on the premises.

These early challenges tested the young city’s resilience and mettle, and it met each test successfully, pushing ahead as the new century dawned. In the early 1900s, new neighborhoods arose on both sides of the river, automobiles now joined bicycles as favored modes of transportation, while. tourism and farming represented the city’s chief economic endeavors. As noted, Twelfth Street was now the city’s most important street, although it was years away from even being asphalt covered. Mixed with the wood frame buildings that bracketed the street were red brick structures hosting some of the city’s most important retail businesses. Miami had shed its frontier ambiance for that of a small Southern town.

New, important projects in the nascent century’s first decade dictated future directions. Henry Flagler, who maintained a “hands on” policy toward his new creation, secured federal funding for the construction of a deepwater channel as well as the creation of the Government Cut, connecting Miami’s new bayfront port with the Atlantic Ocean lying several miles east of it. Flagler was also instrumental in connecting the Florida Keys through the extension of his Florida East Coast Railway to Key West. Additionally, the industrialist was involved in the appearance of a sparkling new county courthouse, which opened in 1904 on a city block donated by him to the county.

Picture of 12th Street looking West taken in 1906. South Florida Photograph Collection, HistoryMiami Museum archives.

In the meantime, the State of Florida was embarking on an ambitious program of Everglades drainage beginning in 1906, with the goal of providing fertile new lands for agriculture. In 1909, a dredge began digging a drainage ditch near the headwaters of the Miami River, and by 1913, this waterway, called the Miami Canal, connected the river with Lake Okeechobee, while the water from the swampland was carried out to sea along connecting waterways.

Everglades drainage, sometimes referred to as Everglades Reclamation, led to the birth of a feverish real estate industry for Miami and most of southeast Florida as large speculators purchased vast tracts of reclaimed land from the State of Florida , then marketed it aggressively in many parts of the nation. The unsavory sales tactics of promoters who sold unwitting investors land that was still underwater, since drainage proceeded slowly, earned for Miami an enduring reputation for marketing “land by the gallon.”

By 1910, Miami’s population had soared to nearly 5,500, while the number of tourists and new business establishments rose sharply. Miami could look to the future with deep satisfaction based on solid accomplishments registered in its years since incorporation.

Fishery and boats docked on the Miami River. Photo taken on July 10, 1922. Matlack Photograph Collection, HistoryMiami archives.