By Paul S. George, Ph.D.

The population of the United States grew from 123 million in 1930 to 132 million in 1940, a 7.3 percent increase, which represented the nation’s lowest rate of growth for any decade before or since. Clearly, the weak growth was one of the ramifications of the Great Depression, as people were hesitant to increase the size of their families with the financial challenges facing many of them.

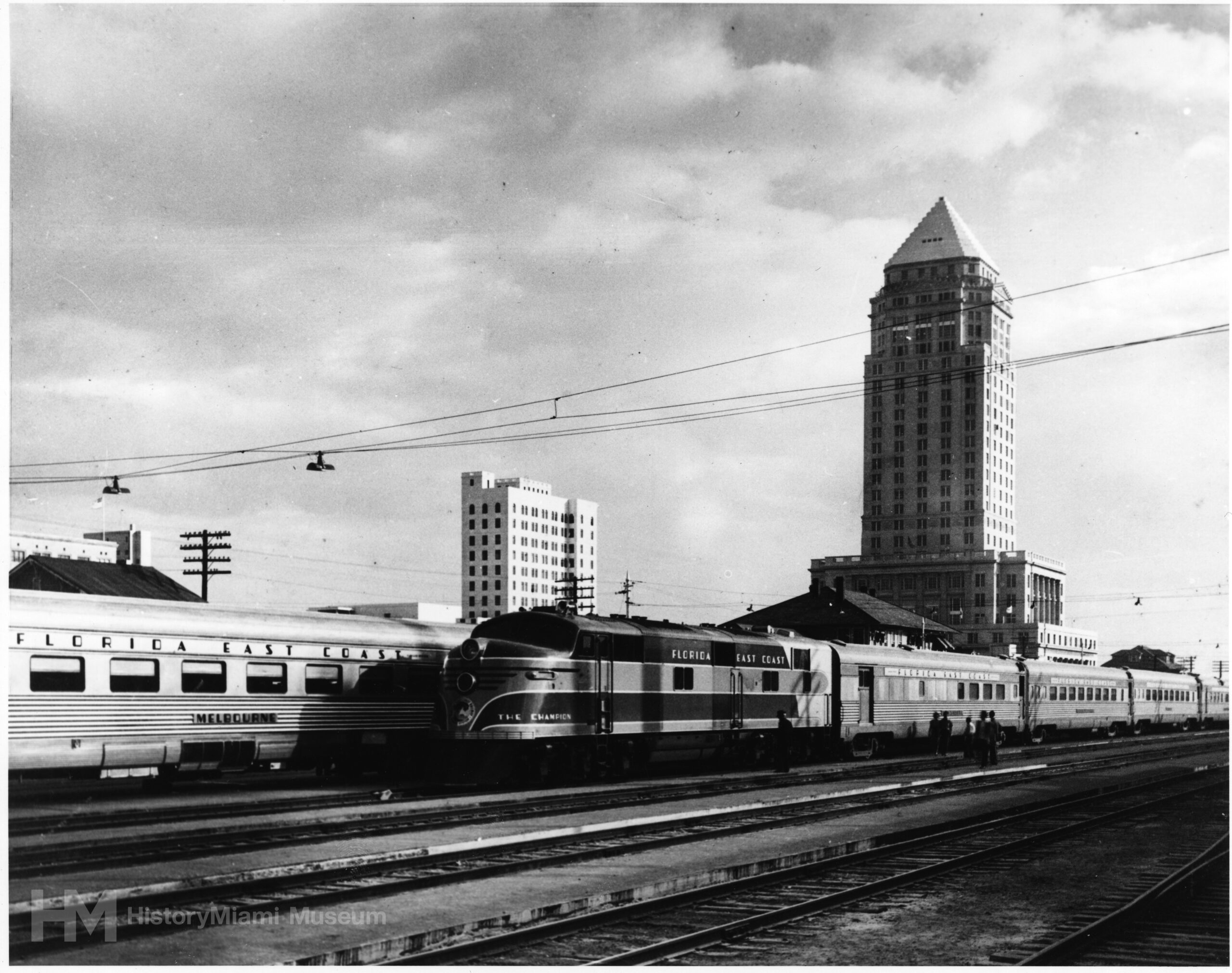

Shows the intersection of Flagler Street and W. 1st Avenue, including the 1904 Dade County Courthouse and the location of present-day Cultural Center. HistoryMiami Museum archives.

But the Depression Decade of the 1930s was, as noted, a surprisingly vibrant time for the Miami area. The City of Miami’s population rose sharply, increasing, in rounded off figures, from 110,000 to 172,000, while Dade County saw its numbers jump from 143,000 to nearly 268,000. Miami Beach, now an ever more important tourist center, experienced a sharp rise in its year-round population, which spiraled from 6,494 to 28,000. The area’s eternal assets of weather and water, combined with the aforementioned growth in tourism, the rise of new industries and a robust construction sector, helped account for this growth.

Flagler Street looking east from NW 1st Avenue, circa 1930. Shows a traffic jam on Miami’s main shopping thoroughfare. Miami News Photograph Collection, HistoryMiami Museum.

The first half of the 1920s represented a breakthrough for the young community of Miami Beach as a tourist resort. But it was followed by the inevitable dip in the numbers of visitors in the aftermath of the boom’s collapse and a ruinous hurricane that struck the area in 1926. Further exacerbating the city’s economic problems was the onset of the Great Depression. By the mid-1930s, however, a rise in tourism, assisted by the attractive American Plan, a hotel package offering affordable room rates and meals, attracted many visitors. Further, major industries, like steel and automobile manufacturing, were becoming unionized, with workers winning benefits like pensions, health insurance and paid vacations. Accordingly, many workers enjoyed for the first time the splendid offerings of Miami Beach.

To meet this growth in tourism and residential population, hundreds of new hotels and apartment buildings were constructed in the second half of the 1930s, most of them south of Lincoln Road, landing the tourist resort, despite its modest population, in the top ten cities in America in terms of the value of building permits issued. For the most part, the architects designing here had been unknown prior to this period. Indeed, it has only been in recent times, with the rising prominence of South Beach’s internationally famous Art Deco district, that the roster of architects from that era, men like Henry Hohauser (Park Central and Essex House hotels), L. Murray Dixon (the Victor and Tides hotels) and Albert Anis (the Winterhaven and Clevelander hotels), among numerous others, has become familiar to aficionados of the new design style, sometimes called streamline or moderne, an eclectic style, influenced by the sleek machines of the 1930s, the decade’s automobiles, trains, airplanes and ships, with their rounded contours and streamlined looks. Many of the hotels lining Ocean Drive and Collins Avenue, as well as apartment houses west of there, exhibit this style, which features eyebrows, vertical and horizontal lines, rounded contours, finial spires, terrazzo floors and the employment of keystone in portions of the building’s facade. Lobbies sometimes showcased the painting wizardry of Earl LePan, with his iconic south Florida flora and fauna images as a backdrop. Today the term “Art Deco” defines this style.

Laying [trolley] car tracks on Pine Tree Drive, Miami Beach. 1925 June 25. Matlack Collection, HistoryMiami Museum archives.

The term “Art Deco” emanated from the famed Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, which appeared in Paris, in 1925, and featured stylized representations of natural forms, employing geometry, vertical lines and an absence of three-dimensional decoration. For Miami Beach and elsewhere, it represents an earlier version of the streamline style, which dominated buildings of the mid- 1930s and onwards.

Since the preponderance of these hotels overlooked the warm waters of the Atlantic, their style reflected that location and included, in addition to the above elements, those of nautical design, such as portholes, ships’ decks, etc. Often, this hybrid style is referred to as Nautical Moderne or Tropical Moderne.

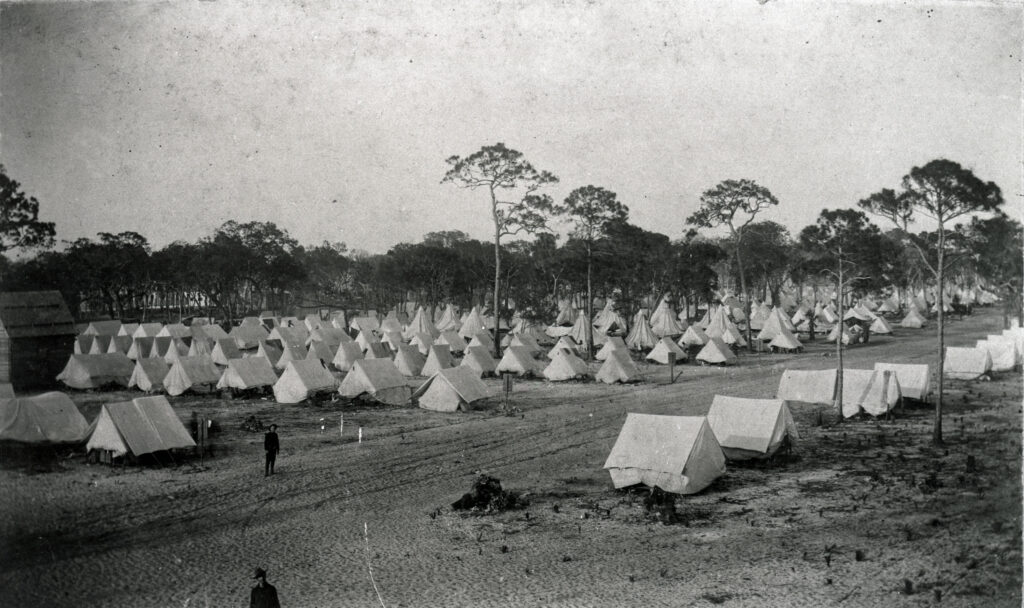

The management of these South Beach hotels looked forward to their best season yet as the winter of 1941-42 approached. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, however, quickly nullified this outlook, leaving ownership and management at their wits end as the nation went to war on December 8, 1941, the day following Pearl Harbor. But by the spring of 1942, greater Miami became a major training center for the nation’s war effort with more than 150 hotels offering thousands of hotel rooms pressed into service as barracks for the Army Air Force officer’s candidate school, an officers training school and a basic training center.

The Esther Weems Docked at the Port of Miami, 1920. Matlack Collection, HistoryMiami Museum archives.

In the meantime, the City of Miami, lying five miles west of “the beach,” was showing signs of recovery, too. An article by Oswald Garrison Villard, in a March 1935 edition of The Nation, spoke to the city’s economic progress during the Great Depression. Villard, a grandson of famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, observed that “If one were to judge Florida by the appearance of Miami one would have to say that the depression is all over in this state. The streets are thronged with the tourists the city must have in order to live, since it has no other trade; the hotels are jammed; the night clubs flourish; there is building everywhere, with lots beginning to go fast; the newspapers are carrying more advertising by one quarter than a year ago; the FERA (Federal Emergency Relief Administration) reports only 4,000 cases…on the relief roll, of whom 1,300 are Negroes and 900 single or widowed women, as against a peak of 16,000 in 1932 and 10,500 in November, 1933. The visitors are spending money freely… “ and “there can be no doubt whatever of the revival of building.” Yet so much remained problematical, headed by rampant gambling, beneath the surface.

The national unemployment rate stood at eighteen percent as late as 1938. The following year Europe was at war and war-related manufacturing eliminated the unemployment crisis in America. Two years later, with the U.S. entry into the war, a new Miami had begun to emerge.