By William D. Slicker

My very dear Jewish friend, Steve Simone, had the chutzpah to die recently. In his memory, I went to Sarasota for a Jewish food festival and ate a homemade apple strudel. Steve would have liked that. While at the food festival, I read a Jewish newspaper. In the newspaper I saw an ad for Wolfie’s Restaurant in Sarasota. That brought back memories of the Wolfie’s restaurants that were popular in Florida many years ago. Those who are old enough to have lived in Florida back when Wolfie’s Restaurants were here, remember the great deli fare: a basket of fresh rolls, chicken soup, dill pickles, reubens, and thick pastrami or corned beef sandwiches.

Wilfred “Wolfie” Cohen also known as The Rascal started his restaurant career as a busboy in the Catskills. He then learned the restaurant business.[1]

In 1947, he moved to Miami, home of the largest Jewish diaspora community in the United States outside of New York City, and opened Wolfie’s restaurant on Collins and 21st Street, Miami Beach. He also opened a second Wolfie’s at Collins and Lincoln.[2]

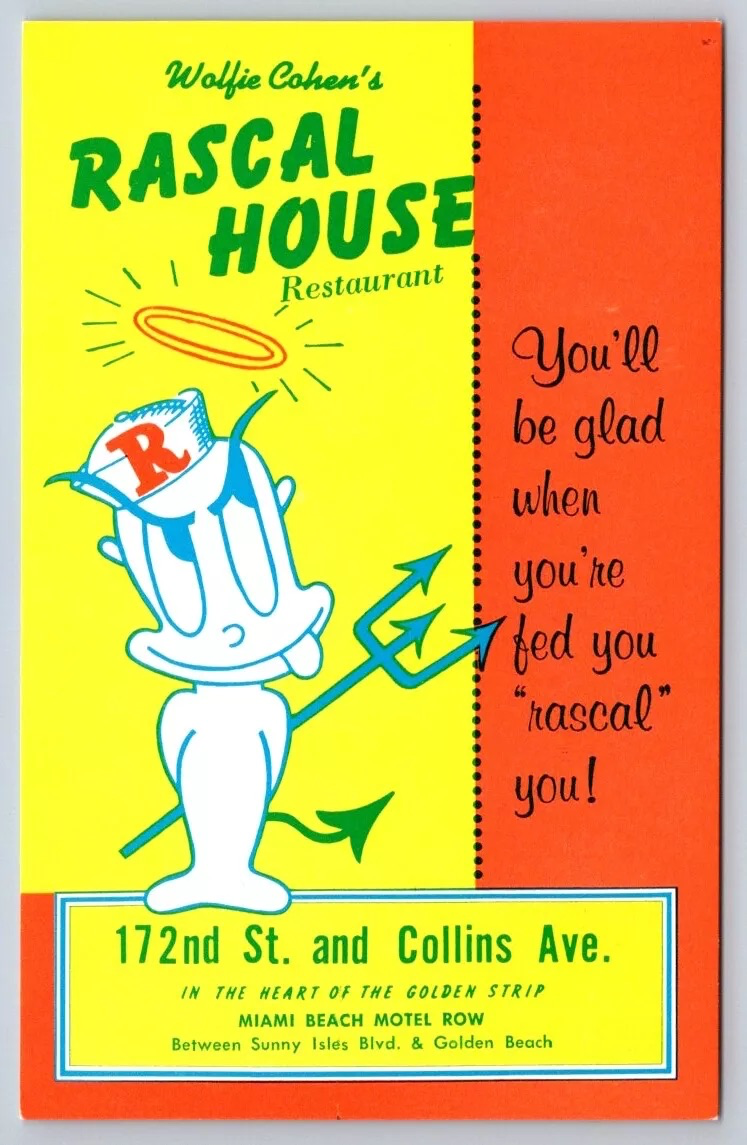

In 1954, he opened The Rascal House on Collins and 172nd Street, North Miami Beach. It was shown in the opening street scene of the Bee Gee’s 1977 video “Night Fever.”[3] Its great food brought in the great stars. It was visited by Frank Sinatra, Jackie Gleason, Judy Garland, Clark Gable, Katherin Hepburn, and other movie and TV stars. It was also a favorite of mafia gangland financier Meyer Lanskey.[4]

For a time, several branch Wolfie’s were open. One location was in St. Petersburg in the plaza at 3200 Central Avenue.[5] Another location was Ft. Lauderdale at 2501 East Sunrise Blvd. A third was located in Cocoa Beach at 900 N. Atlantic Avenue.[6] A fourth was in Jacksonville at New Beach Blvd at Southgate Plaza.[7]

The Cocoa Beach Wolfie’s was featured in the movie Fly Me to the Moon in which Apollo engineers were shown eating there.[8]

Wolfie Cohen died in 1986. Only one of his restaurants survived him. His daughter operated The Rascal House for 10 years and then sold it. It closed in 2008.[9]

There was a short term rebirth of Wolfie Cohen’s tradition on the east coast of Florida. In 1998, Jerry’s Famous Deli opened a Rascal House at 2006 Executive Center Drive, Boca Raton, but it closed shortly afterwards[10]. Then in 2024, a Wolfie’s was opened at 251 South US 1, Suite 1, Jupiter Beach, but it is now called the SaltBird Kitchen.[11]

There is a present rebirth of Wolfie Cohen’s tradition on the West Coast of Florida. JFD Parent LLC’s CEO Jonathan Mitchell opened a Wolfie’s at 1420 Boulevard of the Arts in Sarasota in 2023 and a Wolfie’s Bakery and Take Out at 5318 Paylor Lane, Lakewood Ranch in 2024.[12]

Now with new Wolfie’s open in Florida, a new generation has the opportunity to enjoy the flavors of the Jewish deli food that made Wolfie’s famous. Steve Simone would like that.

[1] Wolfie’s and Rascal House Miami Designed Preservation League, 2022 .https://mdpl.org/archives/2020/04/wolfies-and-rascal-house/; Ingall, Marjorie, The Greatest Floridian Restaurant In the World, Tablet Magazine, (Apr. 14, 2017) https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/the-greatest-floridian-restaurant-in-the-world

[2] Ibid

[3] Wolfie Cohen’s Rascal House, Miami Beach 1970’s Vintage Menu Art -https://vintagemenuart.com/products/wolfies-rascal-house-miami-beach-1970s?srsltid=AfmBOopp1AqLP66BBSxI2Dq2WFItMXC8KAW3GrelWAfOzBqTSr00HTWf; Kiddle Encyclopedia, Wolfie Cohen’s Rascal House Facts for Kids (Oct. 17, 2025) https://kids.kiddle.co/Wolfie_Cohen%27s_Rascal_House

[4] Wolfie’s and Rascal House, supra.

[5] Wolfie’s Restaurant Opening Set for Early December at Plaza, St. Petersburg Time (Nov. 18, 1953); Wolfie’s Restaurant https://www.flickr.com/photos/hollywoodplace/5479345908

[6] Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/edge_and_corner_wear/5561571826

[7] Whitaker, Jan, Famous in its Day, Wolfie’s, Restaurant-ing Through History (Mar. 27, 2011) https://restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com/2011/03/27/famous-in-its-day-wolfies/

[8] Swrup, Aahana, Fly Me To The Moon: Are Satellite Motel and Wolfie’s Restaurant Real Places, The Cinemaholic, (Aug. 15, 2024) https://thecinemaholic.com/fly-me-to-the-moon-satellite-motel-wolfies-restaurant/

[9] Wolfie’s and Rascal House, supra.

[10] Karetneck, Jan, Worth the Wait, Broward Palm Beach New Times, (Aug, 13, 1998), https://www.browardpalmbeach.com/food-drink/worth-the-wait-6336771/; Yelp, Rascal House Restaurant, Boca Raton, Florida https://www.yelp.com/biz/rascal-house-restaurant-boca-raton.

[11] Yelp, Wolfie’s-Jupiter-Florida, https://www.yelp.com/biz/wolfies-jupiter; Metrodesk Media, Jupiter Restaurant “Saltbird” Opens with Comfort, Creativity, Boca News Now (2026) https://bocanewsnow.com/new-restaurants/jupiter-restaurant-salt-bird-opens-with-comfort-creativity/

[12] The Original Wolfie’s Restaurant ,About Us https://originalwolfies.com/story; The Original Wolfie’s and Wolfie Cohen’s Rascal House, Jerry’s Deli, https://www.jerrysdeli.com; Robinson, a Taste of Tradition, Edible Sarasota, Nov. 8, 2024, https://ediblesarasota.ediblecommunities.com/about-us; Gordon, Mark,, Famous New York-Style Deli Brand Plans Big Sarasota Opening Weekend, Business Obverser, (Oct. 30, 2023) https://www.businessobserverfl.com/news/2023/oct/30/famous-new-york-style-deli-brand-plans-big-sarasota-opening-weekend/.