My father, Jacob Siegel, came to Florida from Livingston Manor in the Catskill Mountains in New York State. That was in 1925 during the boom in Miami. He and a friend started a concrete block plant in Little River. He went back home to see if the family was well in 1926. He had my mother, brothers George and Harold, and my sister Frances and me. While he was gone the great 1926 hurricane struck and completely wiped out the concrete block plant. He loved Miami and always wanted to return.

In time he had three gas stations on Route 25 in New Jersey: two in Rahway and one in Avenel. When the Depression hit in 1929, the banks foreclosed the mortgages on the three stations and he lost everything again. At that point he decided to start a new life in Florida. My brother George was working on a ship that went from Miami to Argentina so my father brought my mother, my brother Harold and me to Miami. He bought a gas station on Northwest 7th Avenue in Little River.

I was 10 years old and no one wanted to rent a room to anyone with a child. My father then bought what was called a railroad shack in Little River on 79th Street and it had an outhouse in the back yard. Within a week we had indoor plumbing and a bathroom. There wasn’t anything my father couldn’t do. We lived there for about a year and I went to Little River School.

He was looking for something he could do to make a living. He had been a painter and decorator in New York before moving to New Jersey so he started a painting company in Miami, Siegel Painting Company. He painted the Army barracks in Jacksonville and several other Army installations. He had painted some buildings in Clewiston and made many friends there.

One weekend when he was getting ready to return to Miami, he stopped at a gas station and asked them to check a tire on the car. He thought that it was low and might have a slow leak. When he left the station it was getting dark. As you drive past Clewiston there is a small hill. As he was coming down the hill the tire flew off and the car crashed sideways into a tree.

It just so happened to be close to a home where a friend lived. The man heard the crash and came running out. A paint can had fallen from the back of the car and hit my father on the head. The man recognized my father and called out “Oh Mr. Siegel, are you alright?” He helped my father, cleaned him up and took him to the Greyhound bus station so he could get a ride home. When my father got to Miami he just took a bus home. When I saw him come in with a banged head and bloody shirt, I nearly died. He came in the house and took a shower. He then got dressed and sat down to have dinner. He was famished. He ate like he had not had food in a week.

He bought a new car on Sunday and was ready to go back to work in Jacksonville on Monday. This was way before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. We were living in a house that my cousin owned on Southwest 20th Road. My mother was taking care of my cousin’s two children. My father was a member of the Workmen’s Circle and on the Board of Jewish Education in Miami. I was going to Ada Merritt School. We lived there for about 2 years. Later we moved to Southwest 6th Street and 22nd Avenue. I finished at Ada Merritt School and then attended Miami High School.

I used to go to the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) and play ping pong and dance to the songs on a juke box. When we were teenagers we would go to 8th Street to the Puritan Ice Cream Parlor and get ice cream cones and sit outside at a table. While we were sitting there, William Reiser and another boy came and rode their bicycles with their ice cream cones around our table. Bill’s ice cream fell out of the cone. We all laughed but I guess it wasn’t funny. After that Bill started coming to the YMHA to dance with me.

Bill and his parents lived on Ohio Street in Coconut Grove. When they first came to Miami in 1934, they lived near Southwest 27th Avenue. Bill used to go across the street and shoot rabbits in the woods on the west side of 27th Avenue. Bill’s father was a WWI veteran and he belonged to the Harvey Seeds American Legion Post and played a bugle in their marching band.

Bill learned to be a dental technician and worked in a dental laboratory in the Huntington Building downtown. Miami was still a very small town. Then after Pearl Harbor, Miami and Miami Beach became a training area for the Army and Navy. The band from the aircraft carrier Yorktown was sent to Miami to wait for a new Yorktown to be commissioned. It took so long for a new Yorktown to be built that they were afraid to send them back to sea. They became the 7th Naval District band and played at service centers where the servicemen danced. The girls had to be sponsored by an official in order to dance there. Bill enlisted in the Army.

Bill went through maneuvers in North Carolina and when he was ready to be sent overseas, a desperate call came from Camp Cook in California for dental technicians. They had a lone dentist who needed a technician to make gold crowns and inlays for the men who were going overseas. Bill was also an artist and it was simple for the dentist to teach Bill to do preps for the crowns as well.

When he was sure that he was staying at Camp Cook, he came home on furlough and we got married at my parents’ home by a rabbi. We went back to Camp Cook and stayed there until the war ended. We came home to Miami when he was discharged by the Army.

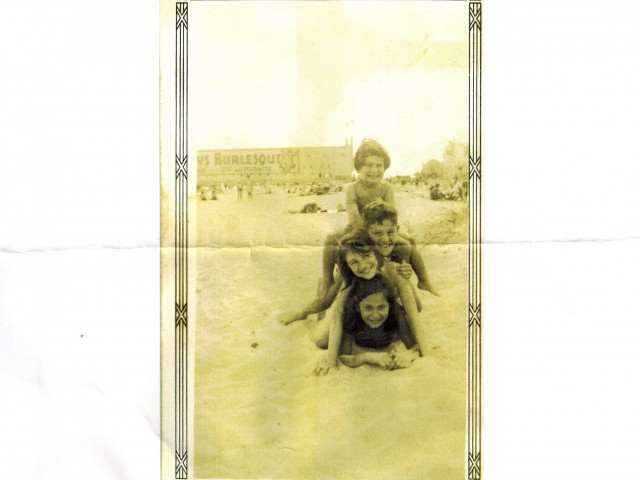

At 92, I still call Miami my home and although times have changed, I still love it here. This is a picture of me with three cousins on South Beach in 1934. That is the “Million Dollar Pier” in the background with the Minsky’s Burlesque sign.