n 1963, I made my first trip to Miami.

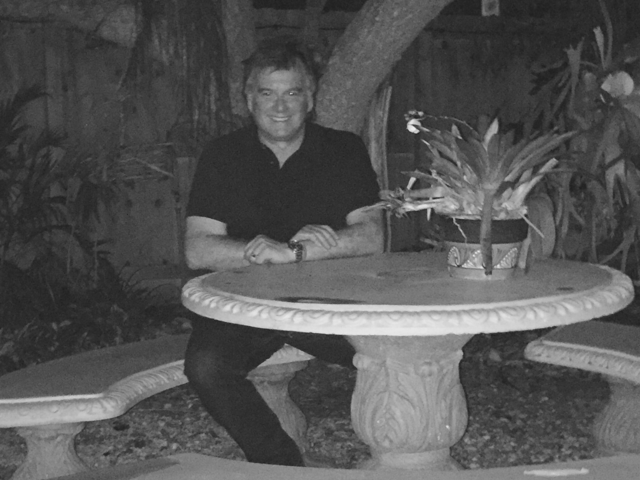

I had just graduated from college and was invited to visit by the man who would become my husband, Richard Rosichan. At the time, he lived in Bay Heights with his parents, Arthur and Claire Rosichan. I was young and had lived my whole life as a northerner. I could not believe my eyes when I saw my first Miami house, filled with beautiful paintings and tasteful décor — the “marble” floors, the den filled from ceiling to floor with books, the tropical patio and what I perceived with my northern eyes as exotic landscaping.

Over time, and as our relationship became more serious, I returned to Miami and was introduced to neighbors and family friends. When we got married, I was teaching school in Buffalo, New York, and Richard quickly finished his degree at the University of Buffalo. For the next eight years, and no matter where we were living, studying and working, we spent every winter vacation in Miami.

My favorite event was going to the sumptuous New Year’s day celebration at a neighbor’s home just down the street. Upon our arrival, we were always handed a glass of homemade eggnog, which in my memory is still the best I have ever had.

My in-laws had no pool, but they used to rent a cabana at the Executive House in Miami Beach. I loved going there and felt like a “fancy” lady. It is hard to believe in this day and age, but when we went swimming, Claire always reminded me to keep my face to the sun so I could go back north with a healthy tan.

Less than 10 years and two children later (Amy and Lori), Richard and I moved to Miami (no more “face in the sun”). By that time, my mother-in-law was suffering from a serious illness. We didn’t want to inflict two active toddlers on our in-laws, so while we were waiting to close on our house, we lived in various places, including an efficiency apartment and two weeks at the KOA campground in Homestead.

While waiting to establish ourselves, we started a small business — Rider-Driver Exchange — a service to connect young folks who needed a ride up north with a driver who needed assistance with driving. We were quite successful in getting people together, putting up signs on a community bulletin board in Coconut Grove, but we had a cash-flow problem. We rarely got paid!

We finally settled in the Buena Vista neighborhood, just north of the Design District. In those days, most of the stores in the Design District were closed to the public. In order to get in, you had to either go with or be sent by a decorator. Richard and I had to be content with just looking. The neighborhood was quiet and sedate, with large two-story houses, but that did not last.

Years after we moved, the neighborhood was revitalized, the Design District became fashionable and open to all, with interesting decorating stores, restaurants and boutiques. During our Buena Vista years, we established new careers, Richard working as a research consultant and I working in the business center of a prominent law firm.

In 1983, we moved to Alton Road in Miami Beach. The city was in decline, and we were lucky to buy at just the right time. In those days, the median was filled with flowers, and the golf course was beautifully landscaped with more flowers. Sometimes wedding parties would stop to have pictures taken with the golf course as a backdrop.

Frequently, passers-by would stop and ask directions to a restaurant, and we were hard pressed as to how to direct them. There was the Villa Deli, a neighborhood institution, and Kim’s Chinese (both now gone), and Bella Napoli and Masters Pizza (still going). In the other direction was a Howard Johnson’s and, of course, Wolfie’s on Collins Avenue.

Lincoln Road was a wasteland, and Ocean Drive was in serious decay. Over time, of course, there was a dramatic turnaround, and the rest is history.

Each of these neighborhoods represents a thousand family dramas, comedic and dramatic, of our family’s life — young love, family growth, teenage turmoil, empty nest and now grandchildren. I have been truly blessed.