My father, John Mantell, was born in 1898, somewhere in Romania. At age 16, he emigrated to the United States and was employed by relatives as an apprentice in the parquet and flooring craft industries.

Industrious and of high intelligence, he quickly became skilled in this craft, learned to speak impeccable English, and adapted quickly to American culture.

Saving his earnings and seeking to capitalize on his newly acquired skills, he accumulated enough to start his own business. In a relatively few years, he developed one of the largest wood parquet flooring company in the United States.

When Dad discovered Miami Beach in 1922, he bought a bungalow with an unobstructed view of the ocean. In those days, people were hesitant to build too close to the ocean, so there were no buildings on Ocean Drive. In effect, our home on the east side of Collins Avenue and Second Street was oceanfront.

Almost all Miami Beach single-family homes at the time were built with coral rock or Dade County pine wood. Our pine home had wide, screened openings around the perimeter instead of windows, which kept out bugs. Canvas covers were rolled down on pipes when it rained.

Even though there was no air conditioning, ocean breezes kept us comfortable even during the hottest summer days.

In those times, no one had dogs or cats. The pet of the neighborhood was a Japanese chicken, which came with the purchase of our house. The chicken lived under our house, which sat on concrete blocks two feet high off the ground.

There were no airlines or interstate highways at the time, so our vacation travels alternated between two available coastal liners. One went from Miami to Savannah to Norfolk to New York, and the other from Miami to Nassau, Bahamas, to New York.

Our family was up north on vacation in September 1926, when a major hurricane hit. Upon our return we fortunately found the bungalow intact, except for some of the screening. Amazingly, the lonely Japanese chicken was still under the house.

The banks caved in that year and the stock market crashed. Dad had retired at age 32, but lost everything except the Miami Beach bungalow in the market crash. So the extended family moved in and Dad went back to work, this time as a general contractor and realtor.

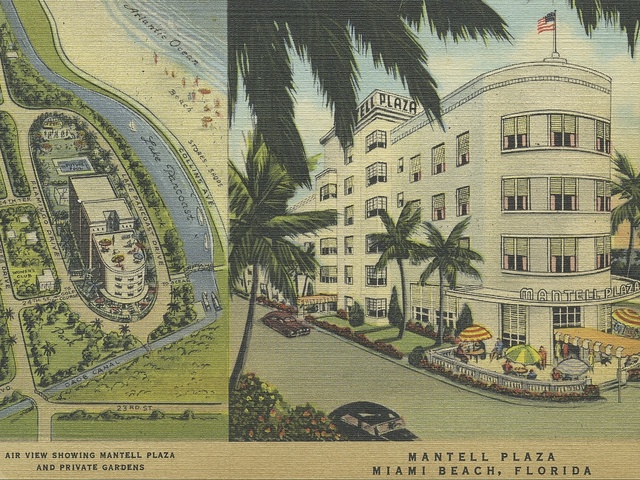

Dad worked with leading architects, building Art Deco hotels, apartments and homes — Flamingo Plaza, Shorecrest and Chelsea Hotel, to name a few. At one time, he was one of the five biggest contractors in Florida. With the help of Seminole Indians and others, Dad had 20 jobs going at once. He built and managed the Mantell Plaza Hotel. Then World War II changed Miami Beach.

In 1942, the U.S. Army Air Forces took over all the hotels, including the Mantell Plaza, for housing Army Air Forces personnel. Miami was troop-training headquarters for U-boats. We would watch soldiers marching the streets, including famous actor Clark Gable. We were very patriotic and I sold war bonds at the local movie theatre. Lucky for us, the Mantell Plaza was the first hotel released by the Army and was the only operating hotel on Miami Beach for a year.

While my father was working to recoup the family fortune, our dear mother Anna was running the household and raising the three children: Murray, Sally and me. We had carefree early childhoods spent barefoot on the golden sands of Miami Beach. I have early recollections of jumping boulder to boulder on the government rock jetties, later the 14th Street beach.

I attended Miami Beach Elementary and Beach junior and senior high schools. It was a small student body; we all knew each other. We had small classes and great teachers. Many thanks to them for all they did for us. After class, there were fun-filled afternoon patio dances and championship basketball games.

In high school, eating off-campus was “strictly forbidden,” so lunches at Joe’s Broadway were dangerous, thus especially delicious. Weekends were for sunburns on the sandy 14th Street beach.

Most weekends, kids took the short jitney to Miami for the movies and big name stage shows at the Olympia Theater (now the Gusman). The favorite lunch spot was Burdines.

My sister Sally also went to Beach High and then University of Miami where she played violin and was a member of the UM symphony orchestra. She met her husband Dan Raylesberg during the war while he was stationed at the Biltmore Hotel.

To date, my brother Murray is the oldest living graduate of Beach High. He studied and got a degree in civil engineering.

During World War II, he was a naval architect, and after the war he became the founding chairman of Civil Engineering at UM, where he taught for 57 years and received numerous awards for teaching excellence.

I started college at the University of Miami in 1946. During my senior year at UM, while doing my teaching internship, the mother of one of my pupils arranged a blind date for me with Norton Pallot. We were married three months later.

Norton was associated with his father, and later his brother and brother-in-law, in the operation of Norton Tire Company, which sold to Goodyear in the 1980s.

Life in Miami has been good. The city has grown and changed beyond recognition, and we enjoy it all the more — and perhaps also because our three children and spouses, and our four grandchildren all live around us in Coral Gables.

(This story was compiled by Laurie Appignani Pallot, as recounted by her mother Gloria Mantell Pallot).