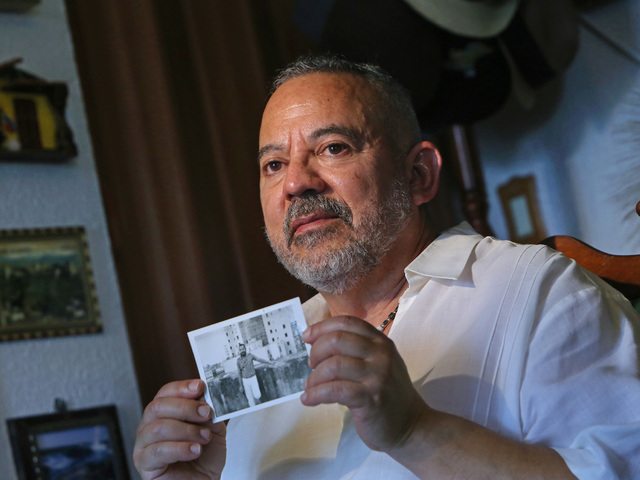

I was born in Guantánamo in 1956. I moved to Havana as a teenager to study and ultimately graduated with a math degree. In 1994, I decided take a raft to the United States.

I had to leave Cuba. I had no future there.

I graduated from the University of Havana believing that if I had a good education and worked hard, I would succeed in life. But because I wasn’t integrated enough with the government, there weren’t opportunities for me. So I resorted to selling produce on the streets with my university degree in my pocket. Later, I cleaned floors at the Hotel Inglaterra.

I also wanted to leave because I valued my freedom and found that I didn’t have the freedom to express myself in Cuba.

I started plotting my escape with a plan to try to get through the border fence at the U.S. naval base in Guantánamo Bay. On Aug. 1, 1994 I went to my 1-year-old niece’s birthday party in Guantánamo. That was the last time I saw many of my family members, including my father. I couldn’t even tell most of them that I had plans to leave. But it proved too difficult to try to get passed security and onto the base.

On Aug. 5th, I returned to Havana to find the streets filled with protesters. Several days later, Fidel Castro announced that whoever wanted to leave, could go. So I got in contact with a cousin who also wanted to leave and we started working on a raft.

When it was ready, everyone in the neighborhood helped us get the raft on a truck we had rented. They wished us well, hugged us and gave us blessings. Many of the old women cried.

We drove the truck to the Brisas del Mar beach east of Havana. Even the people at the beach helped us get the raft out on the water. A neighbor of mine, who had planned on going with us, backed out at the last minute. And my cousin, who was just supposed to help us get out, ended up coming along.

We left on Aug. 30, 1994.

I was the guide on the raft. I had the compass. Before we knew it, the coast of Cuba was gone. We left in the late afternoon so we saw nightfall.

The night out on the water was one of the most impressive things I’ve ever experienced. The only light you see is the moon. We would see empty rafts out on the ocean. I later realized that those probably belonged to people who didn’t make it because when the U.S. Coast Guard rescued rafters, they would usually sink the raft.

We were out on the ocean for the entire night. Our sail didn’t work so our hands were destroyed from rowing all night. Our drinking water had been contaminated and we were too nervous to eat.

There was a point when everyone saw an image in front of us on the sea. I’m not a particularly religious man but, to me, it was an apparition of the Virgin Mary. She stood in the direction that we were supposed to be heading. She came at a time when things were getting desperate for us. Next thing we saw were helicopters.

At this point, night was falling on our second day at sea. We had been out there for a little more than 24 hours.

We were picked up by the U.S. Coast Guard and they took us to a ship that was full of people. We were in bad shape. The ship had the biggest American flag I have ever seen. For me, it was like an angel hugging us and welcoming us to the United States. It was the first time I felt safe since I left Havana’s shore. Even in Cuba I didn’t feel safe. So it was the first time I felt that way in a long time.

I knew there was a chance that I wouldn’t be able to get into the U.S. Nothing was guaranteed. But I had to try. The freedom to express myself and have a voice was worth it.

We were on the ship for about a week. We would travel around the Florida Straits picking up more people on rafts. Then we finally made it to the base in Guantánamo.

We stayed in tents on the sand in extremely hot weather and with barely any clean water. I was in Guantánamo for a little more than two months. With conditions as bad as they were in Guantánamo, they began building camps in Panama. Some friends and I decided to go there.

When I got to Panama, all I had on was shorts and shoes that I had made out of cardboard. I was there for almost four months. In Guantánamo, they were creating better conditions, so that they could send us back.

Finally, I was able to come here to the United States. I arrived on Aug. 31, 1995.

It then became about a new struggle for a new life. I had to adjust to a new language and a new system of living. In Guantánamo, there was a program that taught us about these adjustments. I still work with this program to help other refugees.

My first job here was at a Pollo Tropical; I lasted there two days. Then I got a job at a pharmacy.

I went from a place where nobody was allowed to aspire and where everything was decided for you and given to you, to working at a place with so many products by all of these different companies. I wasn’t used to having so many options.

That was my first dose of the reality of living in the United States. Here, they don’t teach you, they push you to learn. You have to go look for work instead of waiting to be told what to do.

In Miami, I feel at home. I love the Cuban atmosphere, the people and the culture.

Twenty years later, I miss my close family and Havana, where I grew up. But my life here gives me independence. If I had gotten here when I was younger, I would’ve probably flourished more. But I can’t complain. I have everything I need for my life here.

What I want to celebrate 20 years after I fled, is not the fact that I left on a raft but that I now know that every country has the ability to be free. I hope that, in the future, every person realizes their potential in whatever country they’re in. So that they don’t feel the need to leave their lives and the people they love to find freedom.

I don’t want there to ever be a need again for what we did and what we went through. For me, that has been the biggest lesson from the past 20 years. I’m grateful to this country for giving me that lesson.