In 1924, Jo and Frank “Spud” Murphy came to Miami from Port St. Joe in the Florida Panhandle. Originally, they were both from Alabama.

My grandfather is nicknamed Spud, after Irish potatoes. He got an offer for a better job as a bookkeeper to move to Miami. They bought a house in Allapattah and my grandfather took a job with Mill’s Rock Company. In those days, rock pits were blasted using dynamite. In a freak accident, there was a premature explosion and the owner, Robert Mills, and several workers were killed. After this happened, Ed Mills, one of the Mills brothers, took my grandfather in as partner. This became a longtime, well-known, road-building business known as “Murphy and Mills.”

In 1923, Rilla and Tom Murrell decided to move to Miami from Alabama to escape the cold and come down to the wonderful weather and easy-going lifestyle. They bought a house in Miami Springs and opened a beauty salon and barber shop together on the circle. My grandfather, Tom, also became the first postmaster of Miami Springs. My grandparents lived in that house until they passed away. My grandmother always grew a wonderful vegetable garden. Men and women would come from all over to have their hair done by my grandmother.

My grandparents all weathered the 1926 hurricane. Back then, they did not have the knowledge of hurricanes like we do today. My grandfather Murphy was stuck out in the storm at a gas station.

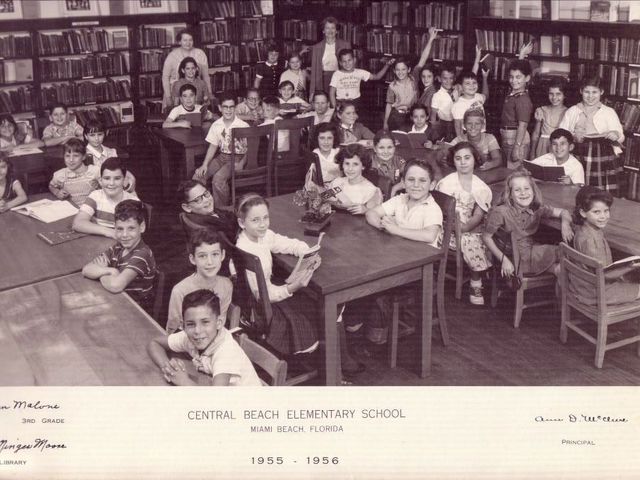

My mother, Ann Murphy Murrell, was born in 1931 at Jackson Memorial Hospital in the Alamo Building, which is still there as a historical site. When she was born, that was the only building at Jackson. She went to Miami Jackson High School and was a majorette in the marching band. After high school, my mom attended the University of Miami.

My father, Lee Murrell, was born in 1930 at his family home. He went to Miami Edison High School where he played football and ran track. He played back in the days when they wore leather helmets and facemasks. They did not even know what a mouth piece was. Can you imagine — they traveled around Florida by plane to play other high school teams?

After high school, he also attended the University of Miami. That is where my mom and dad met; a mutual friend introduced them. They dated for a while and then were married in the First Baptist Church of Allapattah.

My mom worked as a secretary before becoming a housewife. My dad worked for Holsum bakery with his own delivery route. Then in the 1950s, they bought property in North Miami at 131st Street and West Dixie Highway. They bought a Carvel ice cream franchise and built a Carvel shop. This was the beginning of their first business. My parents were living in Allapattah at the time, so to be closer to the Carvel, they bought a piece of property in North Miami and built their first home.

In the 1960s, they sold the Carvel store then went across the street and opened an ice cream and hamburger place called Lee’s. This became the new hangout for the North Miami kids. After owning Lee’s for a few years, the long hours were just too much while raising four kids. My father sold Lee’s and started M&M; Landscaping.

In the meantime, he went to the Lowe Art Museum to take a metal sculpting class as a hobby and also went to Coconut Grove in the 1960s to take a class to learn to make jewelry. Well, a hobby became a business. He was making jewelry and metal sculptures and selling them at arts and crafts shows. He stopped making the jewelry, but he still has his metal sculpture business, Copper Creations by Lee. Now, 45 years later, he is still doing art shows and selling online at Etsy. When anybody asks my dad where he is from, he still says, “My-am-uh,” like a native.

My mother and father had four children. The two oldest were born at Mercy Hospital, and the two youngest at North Shore. We were raised in North Miami when it was just a small town where everyone knew each other. We would ride our bikes everywhere and loved hanging out at Haulover Beach and Greynolds Park. We loved going to eat at Pumpernick’s, and then we would go to the First Baptist Church of North Miami. All four of us graduated from North Miami Senior High; we were true “Pioneers”!

Some of us still live here, and some have moved on. My parents have seven grandchildren, who were all born in Miami. My father has one great-granddaughter. We are University of Miami Hurricanes and Miami Dolphin’ fans. When the Marlins came to Miami, we became big fans of them, as well. My mother was one of their biggest fans, going to almost every game. After the games, we would go to Rascal House to enjoy dinner. She had a room in her home dedicated to all three sports teams. My parents always loved Miami, and my mother believed going to the beach could cure anything.

I have written this story in memory of my mother, who always wanted to write this story. Sadly, she passed away July 29, 2013, so I used her notes to write this piece.