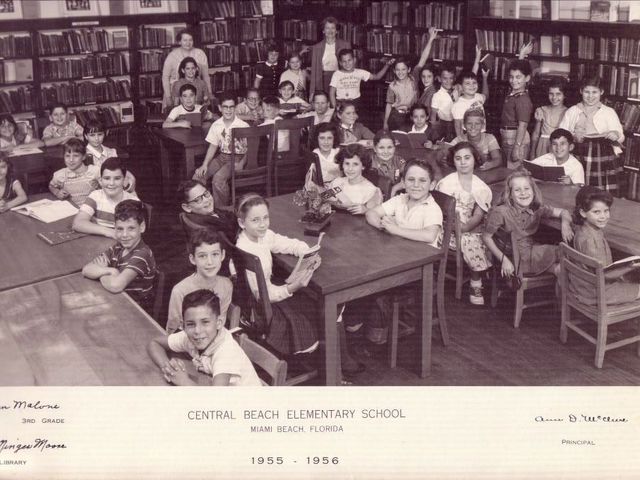

My sister Laurie and I share an unusual trait: we are in our 50s and we are both native Miamians.

We were born at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach. My mother, Suzanne Gillette Collins, and her family moved here in 1939, because my grandfather, Jules Gillette, was seeking new opportunities in Miami.

He opened a men’s clothing store on Lincoln Road, Jules Gillette Men’s Clothing, leading to a succession of such stores on Flagler Street, in downtown Miami, and on Northeast 125th Street in North Miami. During World War II, the store became an Army supply store since Miami Beach was a training ground for soldiers.

My mother helped out at the store and she liked to tell the story about the first time a soldier came in and asked for a jock strap. She was clueless.

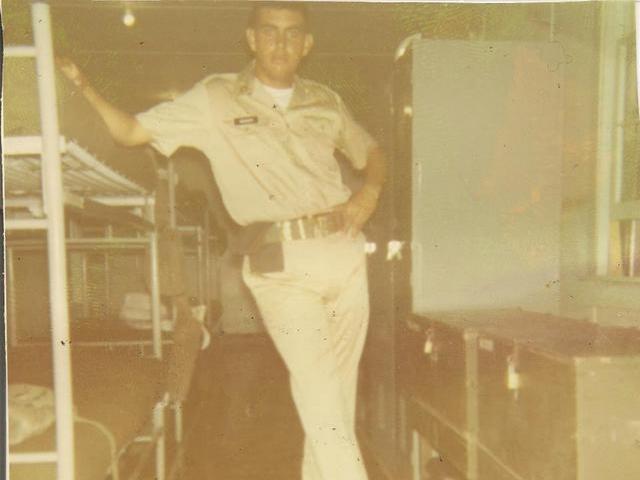

Although he didn’t know my mother at the time, my father, Ken Collins, trained here with the Army Air Corps during the war. He stayed at the Embassy Hotel on Collins Avenue which, like most other hotels, had been converted for wartime use. The soldiers would drill in Polo Park on Miami Beach.

My mother would watch the soldiers drill. My father went on to fly several missions before being shot down over Hungary. He was captured and became a POW in a German prison camp. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army liberated the prisoners and my father went home to Ohio.

He went to college and moved to New York for a career in retailing.

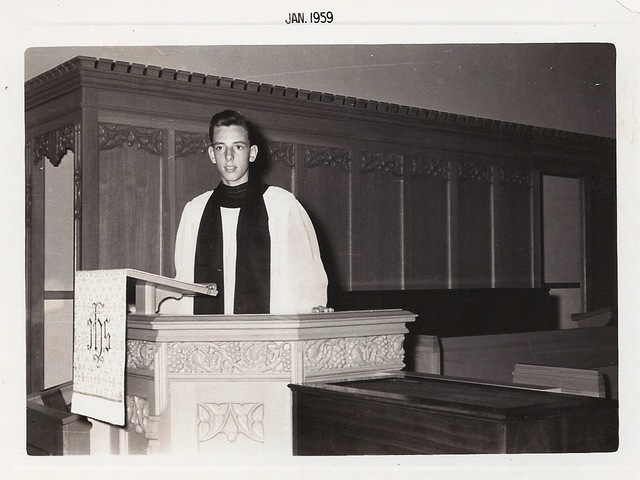

My mother graduated from Miami Beach High in 1945 and went to college out of state as well.

My parents met when they both worked at Macy’s in New York. They married in Miami in 1953, but remained in New York for a couple of years before moving to Miami when my grandfather offered my father a job at his store. On Lincoln Road at that time, there were about eight men’s clothing stores and several ladies’ shoe stores.

My parents found an apartment on Marseilles Drive in Miami Beach. The apartment was not air-conditioned, so they agreed to purchase one if the landlord would install it.

They then bought a house on Northeast 175th Street in North Miami Beach. It was one of two houses built on the block at the time, which ended in a dirt road until about 1962. The stately royal palms in the front of our house came from Miami Beach when they were constructing the Julia Tuttle Causeway.

My parents lived in that house until 1991 when they moved to the Highland Lakes area, where my husband and I also live.

In September 1960, Hurricane Donna threatened South Florida. It was believed that the low barometric pressure might induce labor in pregnant women in their late stages. Since my mother was eight months pregnant with me, she and numerous other pregnant women spent a night roaming the halls of Jackson Memorial Hospital until the hurricane threat had passed.

Since I was to be her second child, she was calmer than most of the women, but she told the story of the many large hysterical women who spent the night with her. It sounded worse than any sorority function you could imagine. I was born in October 1960.

In 1962, there was the Cuban Missile Crisis. We still have my mother’s can of Sterno, and the shovel my dad bought to dig a trench if we needed a latrine. I can’t picture either of them using either device, but they couldn’t say they weren’t ready.

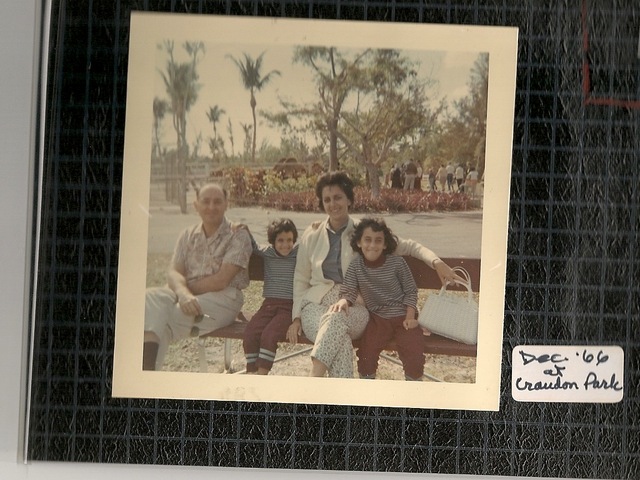

My one grandmother would take us to Junior’s on 79th Street and Biscayne Boulevard, where they had great breads and rolls. My other grandparents used to take us to the Roney Pub for dinner. We loved that big quarter-wedge of iceberg lettuce they’d give you with a choice of dressing.

We’d also go to Corky’s for pastrami and corned beef back in the days when I ate big meaty sandwiches. Corky’s used to have a drive-up area where you could order from your car window, and they’d bring your food out to your car and hook a tray to your car window.

As I got older, I’d go to the Sportatorium for concerts with my friends way out on Hollywood Boulevard, before there was anything else built out there.

My mother worked at Temple Israel, where my family were members. My dad eventually opened his own store in Bay Harbor Islands, Ken Collins Men’s Clothing. I used to help out at both places during summers and holidays.

My sister and I went to Sabal Palm Elementary School, John F. Kennedy Junior High School, and North Miami Beach High School.

Two recollections I have that are not among Miami’s finer moments: in 1972, there was an organized boycott against busing, and parents kept their children home from Miami-Dade public schools for two days. I went to school both days; I think I was one of two or three kids in my class who showed up.

I also remember going to work downtown in the summer of 1980, following the McDuffie riots. I remember seeing the smoke rising from Liberty City – and, visible from Interstate 95, the National Guardsmen with their rifles standing on almost every corner.

I went out of state for college, but came back to the “U” for law school, where I met my husband, Peter Bronstein. I am a die-hard ‘Canes fan and bleed orange and green during football season.

We were married on Key Biscayne at the Sonesta. What a beautiful weekend it was, and our out-of-town guests got a wonderful taste of Miami.

We had a Michigan flag at our wedding, since my husband went to the other U of M for undergraduate studies.

We lost my mom several years ago, but my dad and sister still live close by. Miami is home, and other than my years at college, I’ve lived here all my life. In the winter, the weather is beautiful, and in the summer, the crowds thin out.

What more could you ask for?