Just like so many other Cuban-Americans, we came to Miami to escape the ravages of the Communist regime that had taken over our island-nation.

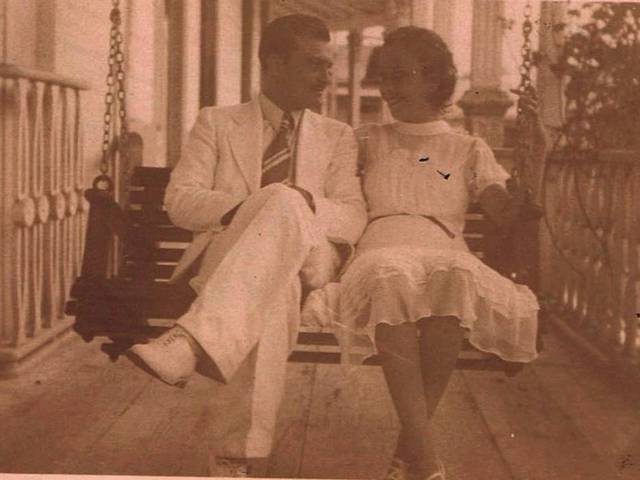

We were lucky enough to still be able to come on a regularly scheduled Pan Am flight. My parents obtained their visas to leave Cuba in November 1961 and were forced to leave their two children behind.

Those were torturous weeks waiting to see if we were ever going to see our parents again. However, God was looking over us and my brother and I took our first-ever airplane ride on December 1, 1961, from Havana, Cuba, to Miami, Florida.

I remember looking out the window and, as we prepared to land, I saw my mother, father and cousins standing on a terrace on the roof of the airport. Little did I know then that this terrace would be one of the places where we would frequently spend Sunday afternoons – it was free entertainment!

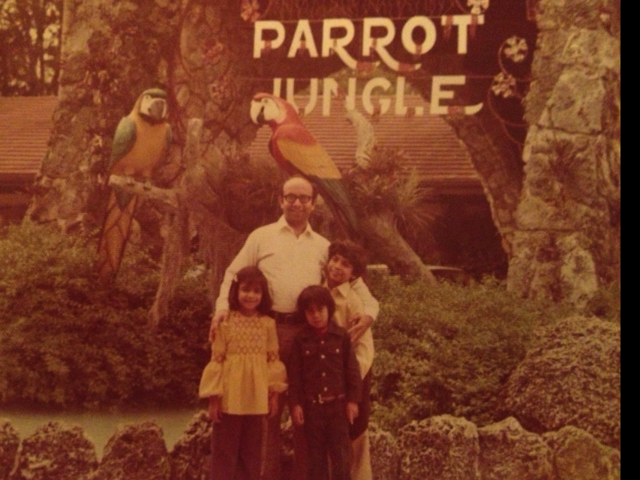

Since we were only able to bring some clothes and had no money whatsoever, our family discovered all the places that provided diversion for my brother, my cousins, and me for free. So we frequently went to the beach (Crandon Park or South Beach), Lincoln Road, the airport, Morningside Park, and Bayfront Park. All these places still exist today, but in a very different way.

South Beach had a dog track right by where Government Cut is and there was no pier. There were rocks that all the kids would climb on and jump from into the water. Lincoln Road was similar to today, but it did not have all the high-end restaurants and it was not as crowded.

There were simple shops, a Carvel Ice Cream shop and a little tram that would take you from one end of Lincoln Road to the other for, I think, 10 cents.

There was no Bayside Marketplace at Bayfront Park – actually, it was really just a big stretch of grass along the Bay. The airport was tiny and you would still have to walk to the tarmac to get on and off planes. The rooftop terrace was very nice to spend time hearing the roar of planes taking off.

Our family settled in what is now called Wynwood. I really do not know if that area had a name then, but I do not think so. We referred to the general area as “el Norwes” (the Northwest). The building that we lived in is actually still there, but the area has changed dramatically.

There was no Miami skyline to be seen and Midtown was not even a thought in anyone’s mind. In fact, having come from Havana, a bustling city with a lot of nightlife and bright neon signs, Miami seemed like a sleepy town then and reminded me more of the town where I was born, rural Moron, Camaguey.

Somehow, it seemed that half of Moron settled within the same block of NW 32 Street. By 1967, when we bought our first house and moved to Hialeah, the entire two blocks between Miami Avenue and NW 2 Avenue seemed to be inhabited by “Moroñeros.”

It was a great childhood there. Everyone knew everyone, we rode our bikes freely without the concerns that seem to worry every parent today, we played “hide-and-seek” throughout the entire block with dozens of kids, and on rainy days we would play Monopoly.

There was no Publix or Dadeland Mall. The only large supermarket in the area was a place called Shell near NW 54 St. We bought our groceries at “Paul’s Grocery Store” on the corner of Miami Avenue and 29th Street and took the bus for a few stops to shop downtown at places like Richards, Kress, Lerner’s, Burdine’s, and McCrory’s. My mother and I loved to have corn dogs at the McCrory’s luncheonette.

I went to Buena Vista Elementary School where I was first called a “spick.” I can still remember the boy’s name: Juan (!). He was taken a little aback by my non-reaction – I had no idea what it meant. I asked him, he explained it to me, and we became good friends. Still not sure what a boy named Juan was doing calling me a spick, though! Fortunately, I never heard the term (nor any other derogatory name) directed at me again.

Later, I went to Miami Edison Junior High, which was bulldozed out of existence several years ago. My brother graduated from Miami Edison Senior High, which was where Edison Middle sits now. We loved going to the Orange Bowl for the Red Raiders games – especially when we played our main rivals – the Stingarees from Miami High.

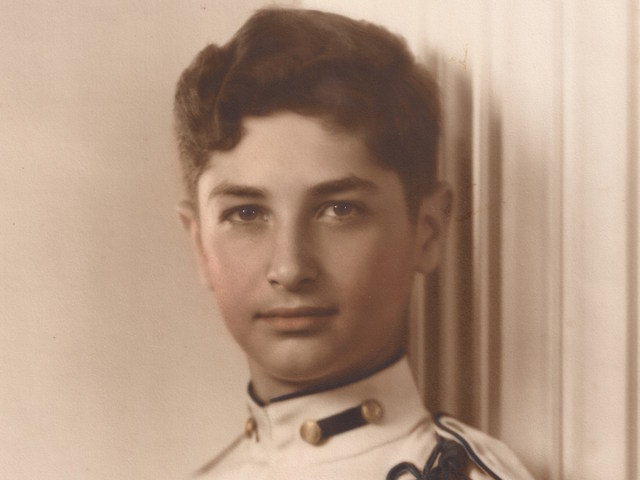

My father was a very resourceful, intelligent, and ambitious man. Within a couple of months of arriving in this great country, he owned his first gas station – on NW 7th Avenue near 50 Street.

The pumps were manned at the time – no self-service then. He provided full service and automotive repair. My mother pumped gas, checked the oil, radiators, put air in the tires, and cleaned the car windows.

After school and during summers, my brother also worked at the station. I always wanted to work there, but my father would not let me – I was a girl and this was well before feminism and the time, like now, when everyone pumps their own gas.

Within a short time, my father owned several gas stations throughout Miami and we saved enough to buy a house in Hialeah. Hialeah had not yet become the Cuban and Latin-American haven it is today. We were actually only the second Latin family on our block in 1967.

My mother, who had never worked a day in her life before coming here, was also incredibly hard-working. Initially, she worked the night-shift at a shoe factory nearby. Her shift started at 11 P.M. and ended at 7 A.M. She would arrive home just in time to get us kids ready for school. She would rest while we were in school, but also clean the house and get dinner ready. Once we were tucked into bed, she would go to work.

Eventually, she was able to transfer to the day-shift. Then she went to school in the evenings to learn to speak English and become a beautician. She received a beautician’s license and opened up her own beauty shop on Collins Avenue and 23 Street.

Both my parents accomplished this when they were already in their forties and fifties, in a new country whose language and culture was totally foreign to them. Hardly anyone spoke Spanish then. Both of their children went to college and received advanced degrees – mainly, I believe, as a result of our parents’ example and expectations.

Although I went away to school and have traveled extensively, Miami remains home and will always be. This is where I grew up, where my parents brought us seeking to raise their children in a free land where opportunity is available for all.

I appreciate all that Miami has given us and I try to give back whenever I am able. Coincidentally, a few years ago I moved to the Morningside area, right down the street from the old park that I used to frequent as a kid. It is still beautiful!